|

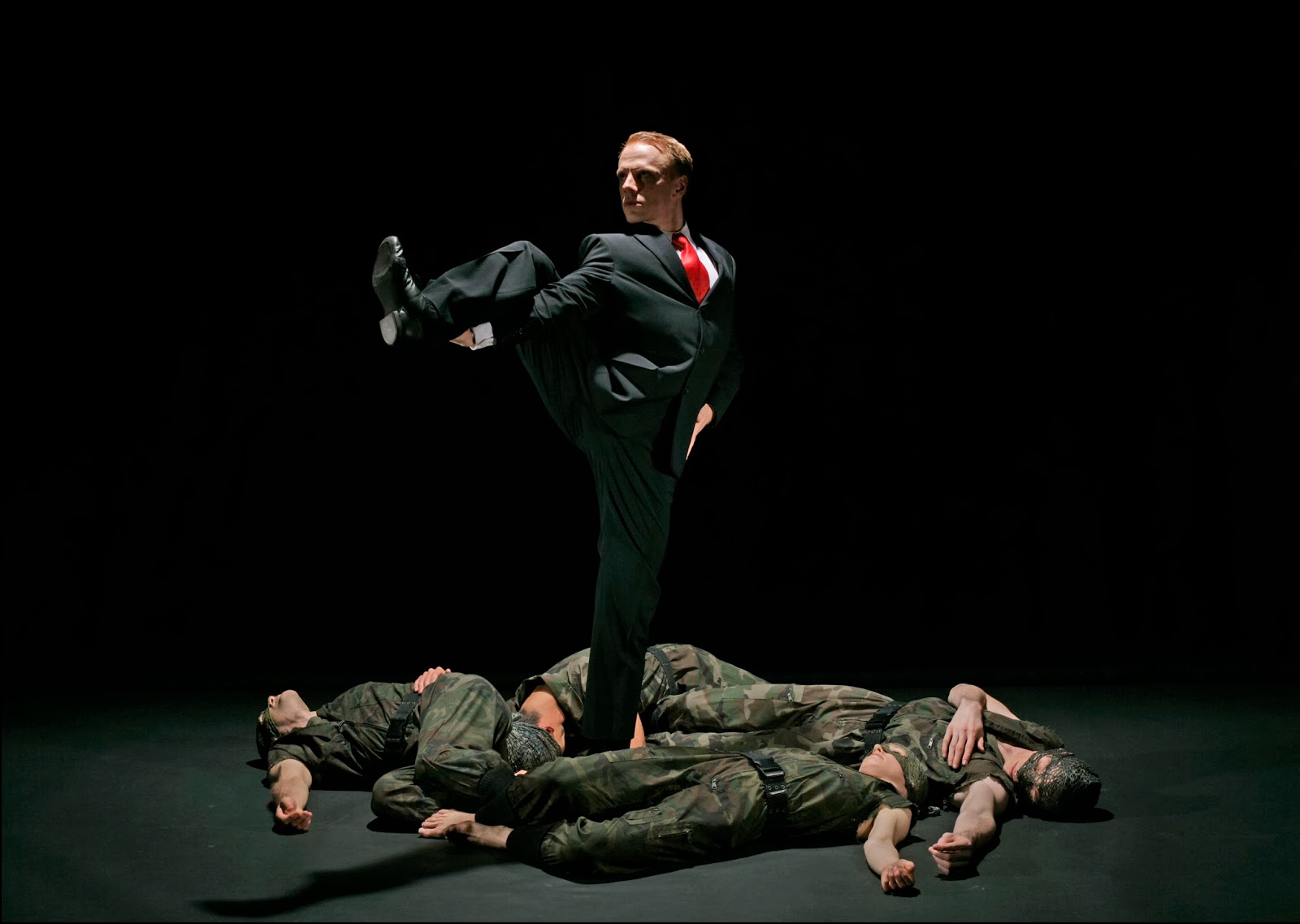

| Shooting star! Cole Horibe as Bruce Lee. Photo: Joan Marcus |

Cole Horibe as Lee, in his theater debut, is the big attraction. Not exactly an unknown, his bona fides include honors in martial arts competitions as well as a stint on So You Think You Can Dance, plus an intangible star quality. The Hawaiian native, who in life speaks with no accent, affects Chinese-accented English, which—impressively—decreases in severity and gaffes as time passes. He has the fleet-footed boxing prance of Lee, as well as steely fighting skills and an implied psychological superiority that gave Lee an instant upper hand. He coils and strikes like a cobra, and deploys plenty of that SYTYCD zazz. (His hair is more Elvis than Bruce Lee bangs, but apparently that was the style earlier in Lee's life.)

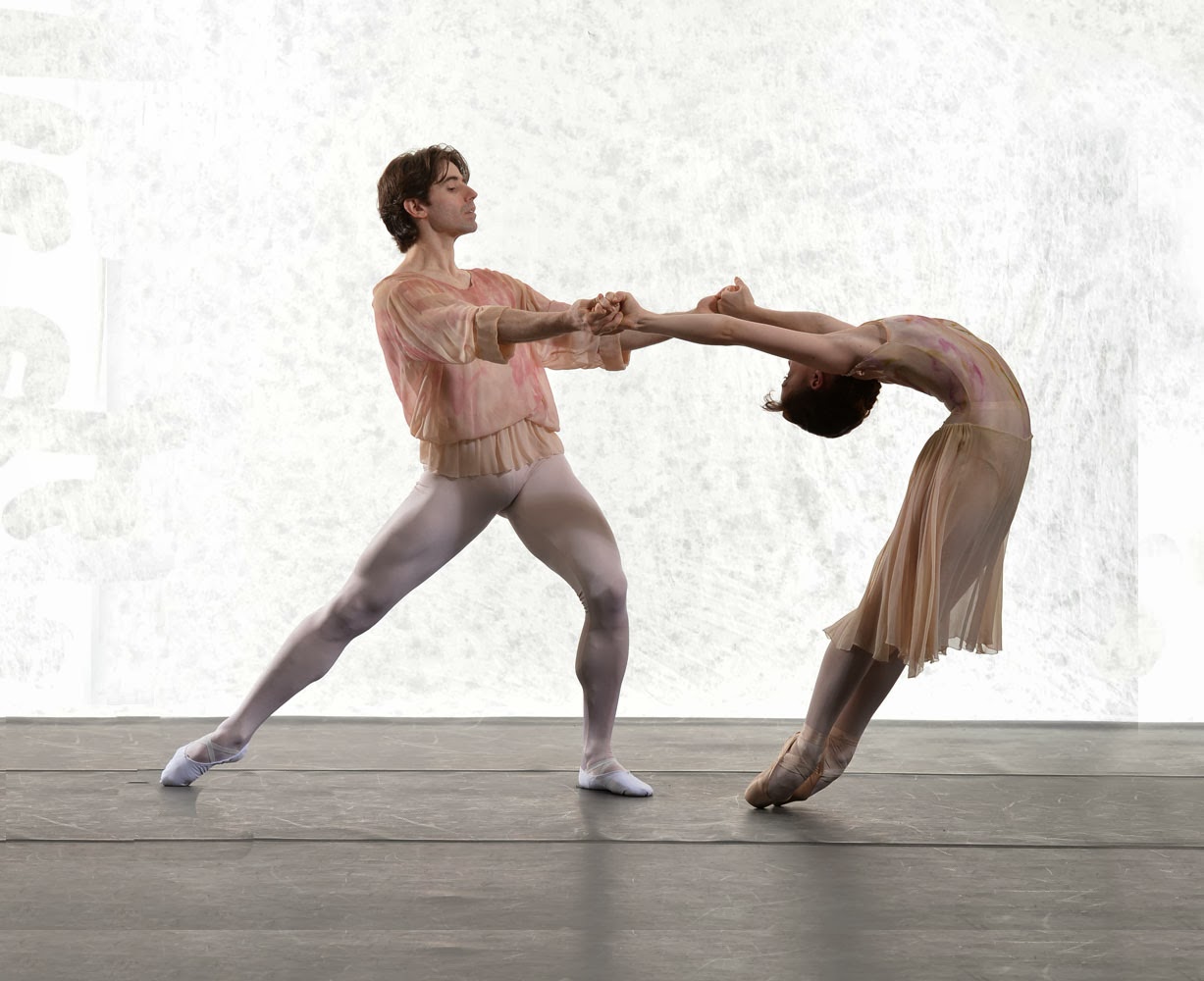

Francis Jue as Lee's deceased father also makes a strong impression, haunting his son in flashbacks and moments of conscience signalled with golden light. Lee apparently fought with his father—a professional clown—throughout his life; a combat scene between the two depicts this conflict, and becomes a metaphor for old generation versus new. Peter Kim's comical physicality allows him to convincingly portray a meek, dorky young man (Toshi) who becomes Lee's confidant, as well as a glad-handin film executive (Dozier).

The production numbers, choreographed by Sonya Tayeh with fights directed by Emmanuel Brown, are the meat of the show, and there are many opportunities to showcase the impressive cast: kung fu class, a dance hall, a funeral and traditionally costumed (albeit in day-glo) parade, and more. Horibe is the sun around which the other planets revolve. He tends to shout his lines for emphasis, but his magnetism and physical prowess are undeniable.

|

| Battling demons and dad. Francis Jue and Cole Horibe. Photo: Joan Marcus |

Act 2 contains a few scenes that drag on, such as when Lee recuperates from his back injury and interacts with his eventually ill-fated son Brandon (Bradley Fong), and when he and James Coburn (Clifton Duncan) travel to India to make a film with no studio support. But for the most part, the two-hour show moves briskly, paced by many production numbers with show-biz dazzle (video here).

The issue of racism recurs throughout the show, as it did in Lee's life. He was cast as Kato in The Green Hornet, which flopped even though Lee emerged as the show's sleeper star. A show developed as a vehicle for Lee, called The Warrior and retitled Kung Fu, wound up starring caucasian David Carradine in part due to a severe back injury Lee suffered, as well as lingering racism against Asians in general painted with a broad anti-Japanese brush. (I presume Hwang chose the same title as a little karmic recalibration.) After rejecting Asia for most of his life, Lee was forced to return to Hong Kong to pursue his brief film career; he made just one, albeit important, film in the US—Enter the Dragon.

Even if he hoped so, he couldn't have known that his name would become synonymous with martial arts action films even decades after his death by cerebral edema at the age of 32. And yet, the fame he had envisioned since he was a boy lives on in this entertaining production that draws on action heroes, the American dream (and compromises therein), and good old show biz.

Additional production credits: set design: David Zinn; costumes: Anita Yavich; lighting: Ben Stanton; sound: Darron L West; projections: Darrel Maloney; composer: Du Yung.